While the Colorado sales tax generally applies to retail sales of tangible personal property and select services, recent Department of Revenue (DOR) guidance has led to uncertainty on the question of whether the tax can be levied on a house. And that’s only the beginning of the issues surrounding construction work in the state.

While the Colorado sales tax generally applies to retail sales of tangible personal property and select services, recent Department of Revenue (DOR) guidance has led to uncertainty on the question of whether the tax can be levied on a house. And that’s only the beginning of the issues surrounding construction work in the state.

The contractor’s rule

The general application of sales and use tax to contractors and construction services in Colorado is detailed in a special regulation commonly called “the contractor’s rule.” The rule defines a contractor as any individual or entity “who performs construction work on real property for another party under the terms of an agreement” — which includes building, road, grading, excavating, electrical, plumbing, and heating contractors. And one additional note is subcontractor has the same meaning as contractor.

Contractors working on real property contracts must pay state sales tax on their purchases of tangible personal property for use in those contracts. Two concepts drive that theory. First, when a contractor constructs a house, the tangible personal property has been consumed in the creation of real property. In short, the contractor is the end user of the tangible personal property and, as such, must pay sales tax. Second, the contractor of real property has traditionally been seen as providing a nontaxable service — a construction service — as services are generally not taxable in Colorado.

The principle that the contractor is the ultimate end user and consumer of tangible personal property used in constructing real property was established when the Colorado Supreme Court held in Craftsman Painters and Decorators Inc v. Carpenter that contractors in a lump-sum bid were selling complete jobs, not separate gallons of paint, lighting fixtures, or pieces of electrical wire to homeowners:

“We think...that when they purchased the several items of personal property and built them into the structure as an integral part of their entire contract, and then disposed of the completed work to the owner, they were users and consumers and not retailers to the owner of each item, [and that this conclusion] is absolutely irrefutable on any basis of logical reasoning, and that authority to support it is no more essential than is authority to support the conclusion that black is not white, or that two plus two equals four.”

However, if a contractor transfers a title to the tangible personal property before or separate from its incorporation into the real property, then the transaction is deemed a retail sale of tangible personal property subject to sales tax.

The DOR labels contractors that perform multiple business activities as “retailer-contractors.” For example, a plumbing contractor may have a retail outlet where it sells plumbing supplies over the counter, and it may provide repairs and bill customers separately for time and materials (T&M). When services and materials are separately stated, sales tax is charged only on the price for the materials and not the labor. The over-the-counter sales and the T&M billings are clearly retail sales subject to sales tax. However, the construction work on 300 new homes is construction work on real property — not a retail sale. Thus, the retailer-contractor must pay sales tax on the materials for the real property construction but charge sales tax on its retail sales. So how does the retailer-contractor keep track of what should be purchased tax-free for resale and what should not?

Because a retailer-contractor may not know at the time of purchase whether an item will be sold over the counter, used in a T&M job, or used on a real property contract, the retailer-contractor should purchase everything free of tax as inventory. It then charges sales tax on its over-the-counter and T&M sales and accrues use tax on the materials withdrawn from inventory for use in real property contracts.

Finally, the contractor rule identifies items that are always deemed retail sales of tangible personal property regardless of how they’re billed. Those are “over-the-counter units not made to order, with an agreement for installation of the unit.” Those unit sales include “sales of stoves, refrigerators, furnaces, air conditioners, washing machines, dryers, carpets, electrical fixtures, ready-made cabinets, storm doors, garage doors, storm windows, screens, sod and similar items.” Not surprisingly, debates have arisen over whether items such as wall-to-wall carpeting, sod, kitchen cabinets, and garage doors are really units “not made to order.” For example, the Colorado Court of Appeals struck down the DOR’s attempt to require a garage door contractor to treat its sale and installation of garage doors as retail sales rather than construction contracts.

The risk to contractors improperly characterizing a transaction can be substantial. For example, if a contractor provides and incorporates kitchen cabinets in new homes under a lump-sum contract, an auditor may treat it as a retailer and assess sales tax on the total amount charged. While the contractor would receive credit against the assessment for the sales tax paid on its purchases, it would owe tax, penalties, and interest on the difference between the lump-sum bid and the purchase price of its cabinet materials. Consequently, if there is any ambiguity regarding the proper treatment of the contract, the contractor is safer by billing the job as T&M, separately stating the two, and charging sales tax on the materials. Such an alternative may unfortunately put the contractor at a competitive disadvantage.

Fixtures or tangible personal property

In addition to applying the over-the-counter unit rule, the scope and nature of what constitutes a fixture isn’t clearly defined for Colorado contractors. Building materials are tangible personal property that, when combined with other property, “loses its identity when it becomes an integral and inseparable part of the realty, and is removable only with substantial damage to the premises.” Items commonly classified as building materials include bricks, cement, drywall, piping, flooring, insulation, steel, paint, siding, and lumber.

Fixtures are adjunct items of tangible personal property that are attached to the real property but do not lose their separate identity. Fixtures might include burglar alarms, window air conditioners, awnings, home theaters, and window treatments such as venetian blinds. Many of the items identified by the DOR as over-the-counter units are arguably fixtures. The department has aggressively treated tenant finishes and any trade fixtures used by a business as taxable tangible personal property. For example, the director held that bowling lanes — bolted and nailed down to flooring that couldn’t be removed without destruction — were subject to tax as tangible personal property because the purchaser treated them as such for federal income tax purposes.

Building permits

Many Colorado cities and counties don’t follow the state’s contractor rule, which requires contractors to pay tax upfront with the issuance of a building permit. The tax paid is an estimate and usually 50 percent of the entire project’s value. Thus, a 3 percent use tax on a $500,000 home would be $7,500 ($250,000 x 3%). The jurisdiction often requires a true-up between the estimate and the actual costs once the project is completed.

To avoid paying the local tax twice, the general contractor should provide a copy of the building permit to any subcontractor providing significant materials. For example, if the framing subcontractor doesn’t have a copy of the permit when it purchases lumber, it would have to pay both the state and local sales tax. But if presented with a building permit, the vendor would only charge the subcontractor state sales tax because the local tax has already been paid with the permit. Unfortunately, many contractors and their subs are unaware of that policy.

Contractors must also follow specific reporting policies on the equipment brought into a local jurisdiction. For example, a contractor would owe city use tax on a crane it brought into a city for use in construction. If local sales or use tax has already been paid equal to or greater than the current jurisdiction’s tax, no additional tax is due. However, if no local tax was paid or was paid at less than the rate in the current jurisdiction, additional tax would be due based on the value of the equipment, its age, and the duration of its use in the city. Failure to file the proper declaration forms with the city may result in tax assessed on the original purchase price with no adjustment for age or time used in the city.

Finally, many home rule cities take a much broader approach to fixtures, and a few insist that anything other than the foundation, walls, and roof are fixtures subject to retail sales tax. In fact, one home rule city auditor even attempted to assess retail sales tax on a roof, arguing that it was a fixture and not construction of real property. Perhaps the auditor believed in selling houses at retail.

Selling a house at retail?

Speaking of which, Colorado’s latest publication, Components of Contractor Compliance, is causing additional confusion among contractors. The confusion is prompted by the DOR’s statement regarding billing procedures, which says that “a contractor’s tax obligation depends on the type of contract the contractor uses. A contractor is treated as a buyer/consumer if using a lump sum contract but treated as a seller if using a time-and-material contract.”

Does that mean that type of contract, lump-sum or T&M, solely determines how tax is applied to a construction contract? Not exactly. As noted, the contractor’s rule itself provides that an over-the-counter sale of a complete unit not made to order — that is, some fixtures — is a retail sale even if billed as a lump sum. But what about building materials that aren’t fixtures? Based on the example in the publication, a contractor could apparently construct an entire house on a T&M basis. Here is the example:

Contractor enters into a contract with homeowner to build a garage for $29,000. Contractor purchases $15,000 of building materials, such as lumber, roofing materials, and wiring from suppliers, and the contractor picks up from these materials suppliers.

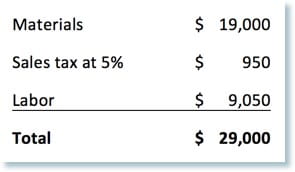

According to the DOR, if the contractor signs a T&M contract with the homeowner, it purchases the building materials free of tax, marks up the materials by $4,000, and charges the homeowner sales tax of $950 on the $19,000 ($15,000 + $4,000). Thus, the T&M invoice would look like this:

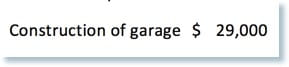

However, if the contractor bids the project on a lump-sum basis, it wouldn’t charge the homeowner separately for any sales tax but would pay sales tax of $750 ($15,000 x 5%) on the purchase of $15,000 in materials. The lump-sum invoice would look like this:

There are two observations about that example. First, the T&M contractor’s net income is obviously higher than that of the lump-sum contractor because the latter is paying tax on the materials, and the former is passing it on to the customer. Thus, the net income of the T&M contractor is $14,000 ($29,000 - $15,000), and the net income of the lump-sum contractor is $13,250 ($29,000 - $15,000 - $750). All other things being equal, billing the construction as a T&M contractor is preferable.

The second observation is simply: is the DOR really indicating that a Colorado contractor can bill construction on real property, like a garage, on a T&M basis?

Because Colorado receives more sales tax from the T&M billing than from the lump-sum billing, it’s clear the state won’t challenge such a treatment. Nevertheless, isn’t this inconsistent with the state Supreme Court’s decision in Craftsman Painters, that the contractor isn’t selling so many buckets of nails, so much drywall, lumber, electrical work, roofing, trusses, siding, and gallons of concrete for flooring, but is using and consuming those materials in the construction of a completed project — that is, real property?

The example raises other questions as well. Can a contractor turn a cost-plus contract into a T&M contract by charging sales tax on each itemized material cost rather than paying tax on the purchase of each item?

Right or wrong, it’s common practice for small contractors in Colorado to pay tax on their purchasesand bill T&M to the client without marking up the materials or charging sales tax on them. Instead, the contractor bumps up the labor cost by the amount of taxes paid on the purchases. If audited and assessed sales tax on the separately stated materials, the contractor then claims credit for the tax already paid; because the materials aren’t marked up, the sales tax that should’ve been collected is equal to the sales tax paid, and the credit eliminates the assessment. The competitive disadvantage to bumping up the labor side of the T&M contractor is slowly disappearing as the practice becomes more widespread.

Does the DOR’s example provide additional cover for such a practice? Will some contractor build a $500,000 home on a T&M basis? And will the department, homeowner, and courts be comfortable with that? No one knows.

This article was originally published on State Tax Notes (login required).